A.S. v Australia (HRC, 2021)

Violations: ICCPR art 7, ICCPR art 9(1), ICCPR art 9(4), ICCPR art 10(3), ICCPR art 17

Unremedied

Unremedied

The UN says:

HRC (2021)[Australia] is under an obligation to provide the author with an effective remedy. … In the present case, [Australia] is under the obligation, inter alia, to provide adequate compensation and appropriate measures of satisfaction to the author for the violations suffered.

[Australia] is also under an obligation to take steps to prevent similar violations in the future.

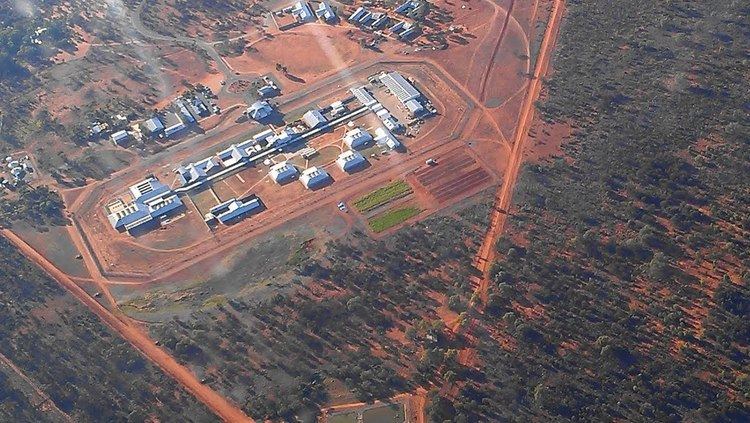

Alice Springs Correctional Centre, a medium-to-maximum security prison for males & females, located 25km from Alice Springs in Australia's Northern Territory & managed by the NT Dept of Justice (photo: Alchetron)

A.S. is an Aboriginal man who suffers from cognitive impairment and mental illness and has a history of hospital admissions both for medical and psychiatric treatment. In August 1995, he was arrested for murder, robbery and attempted sexual intercourse without consent. In October 1996, he was found not guilty on each count on the ground of insanity. He was ordered to be imprisoned at Alice Springs Correctional Centre, pursuant to Section 382(2) of the Northern Territory (NT) Criminal Code.

In 2002, the NT amended its Criminal Code, inserting Part IIA ‘Mental Impairment and Unfitness to Be Tried’, which permitted custodial or non-custodial supervision orders for people found not guilty by reason of mental impairment. A.S. was deemed to fall within the meaning of Part IIA. He remained imprisoned (in 'supervised custody') in Alice Springs for over 20 years until November 2015, when he was transferred to Darwin Correctional Centre, another maximum-security prison.

A.S. claimed that his rights under article 2(1) (non-discrimination), article 7 (torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment), article 9(1) (liberty) and article 9(4) (habeas corpus), article 10(1) (humane treatment of prisoners), article 10(3) (prisons must aim to reform and rehabilitate), article 17(1) (interference with family), article 23(1) (protection of the family), article 26 (equality before the law) and article 27 (minorities’ rights to culture) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) had been violated by Australia as a result of his arbitrary, indefinite detention in a maximum security prison, without accommodation of his mental disability needs.

The Committee determined that the custodial supervision of A.S. is akin to preventive detention and that such detention presents severe risks of arbitrary deprivation of liberty. States must show there are no alternative measures; that the detention doesn’t last longer than absolutely necessary and that the State fully respects article 9. The Committee emphasised the need for prompt and regular review by a court or other similar tribunal as a necessary guarantee for those conditions.

The Committee found that A.S.’s detention had been arbitrary in violation of article 9(1) and that his inability to challenge the justification for his continued detention for preventive reasons constituted a violation of article 9(4).

Given the inappropriate conditions of A.S.’s detention for most of its duration, and its indefinite duration in the absence of mandatory reviews in adversarial proceedings, the Committee held that serious psychological harm had been inflicted on A.S. contrary to article 7. In the light of this finding, the Committee did not examine the same claims under article 10(1) (humane treatment of prisoners).

Regarding A.S.’s claim concerning insufficient services for his reform and rehabilitation throughout most of his custodial supervision, Australia was also found to have violated article 10(3).

Finally, the Committee found a breach of article 17 (interference with family) in the absence of evidence of efforts to facilitate contact between A.S and his family between 1995 and 2013. In the light of this finding, the Committee did not examine the same claims under article 23. It also held that the author failed substantiate his claim under article 27 (minorities’ right to culture).

There does not appear to be a follow-up report nor further information on, or any remedy provided to A.S., in spite of the Committee requesting follow up within 180 days.

Read the full decision: A.S. v Australia (July 2021)